The term “quarantine” or “Hospital tank” can mean different things to different aquarists. To some, it s a sterile-looking, medicated, a bare tank that houses new fish for a day or two to see if any disease develops, and to others, it’s a second, fully set-up, a smaller tank that maintains new fish and invertebrates for several weeks to be sure all is well before introduction to the main tank.

Both methods have their advantages and disadvantages. The bare tank allows the effective use of medication, good observation of the fish, and the opportunity to keep the tank bottom clean. However, the fish cannot survive long or well in such a setup, and the water should be discarded after each use. In my opinion, the bare tank finds its best application as a treatment tank, for use when a disease has been detected and a course of medication determined.

How do I set up a quarantine

tank?

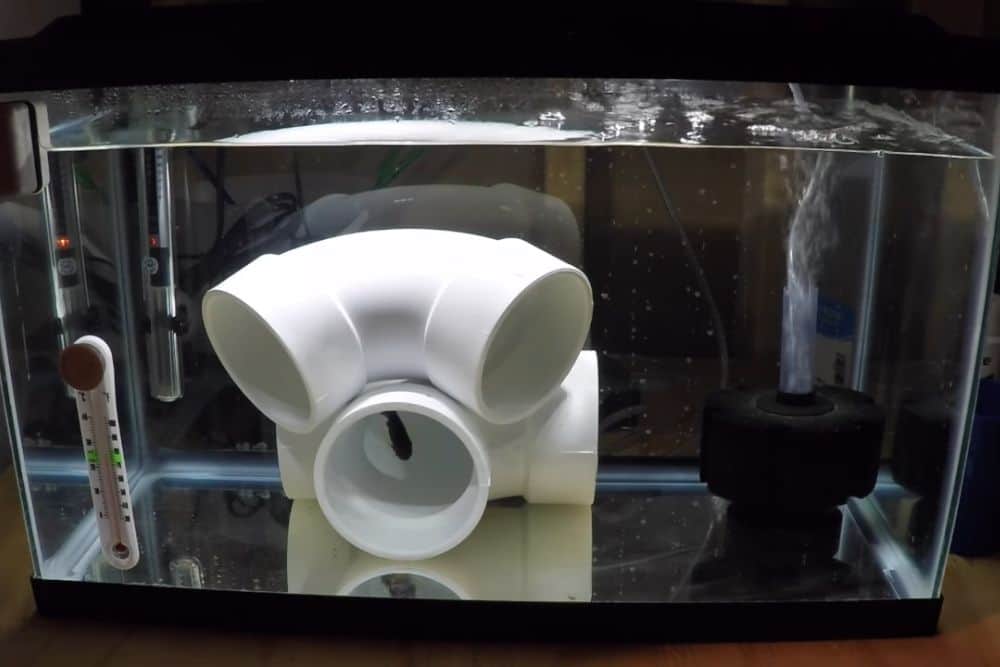

A quarantine tank is usually a small tank that is rather sparsely decorated, which means no substrate or plants. To provide hiding places in a quarantine tank, use only decorations that you can disinfect or boil, such as a piece of driftwood or a clay pot.

A small filter and a heater complete the setup. Place your new fish into this tank for two to four weeks. Observe the animals and their behavior carefully during this period.

When in doubt, have the fish examined by an expert before you add them to your regular aquarium. If the fish actually do have a disease, they will have to stay in the quarantine tank while they are being treated.

They must remain there until you can no longer see any signs of illness. Then you must clean and disinfect the quarantine tank thoroughly, including decorations and equipment, after you move the fish.

What should be the size of the quarantine tank?

A small tank, 10 to 30 gallons, set up with a biological filter and some tank decor for hiding, is more functional for quarantine than a bare tank. It allows a new fish to be maintained under good aquarium conditions for two to four weeks to get used to the water, the tank routine, and available foods away from the competition of the main tank.

If a fish does bring a problem home with it, this should be evident within two or three weeks and, depending on the disease, treatment can be effected in the quarantine tank or in a bare treatment tank. A small quarantine tank is a lot easier to keep free of disease than a large display tank, and can be used to brighten up another corner of the room. Also, if necessary, a 0.2 ppm copper treatment level can be better maintained in a small tank that does not contain calcareous gravel or rock.

An important side benefit of using an emergency quarantine tank is that a new specimen can be target fed without competitors present. An established community of fishes may make it difficult for a newcomer to get enough to eat at first, and if the fish has been underfed during shipping it may go into a downward spiral, hiding and losing strength. A few weeks in the peaceful isolation of quarantine allows it to become well-nourished and get accustomed to the water and foods you provide.

Why must I keep my new fish in quarantine?

It is not uncommon for a disease to be introduced into a tank along with apparently healthy new fish. To prevent this, you should keep your new arrivals in a separate quarantine tank for the first two to four weeks.

Typically, disease symptoms will appear two to fourteen days after you have purchased the fish. Even if the new arrivals look healthy, they can carry parasites, bacteria, or viruses that may infect the other fish.

All of your original fish could get sick or even die if they cannot cope with the pathogens brought in by the new fish. Of course, a quarantine tank does not give you a 100 percent guarantee against the introduction of diseases, but it does reduce the risk considerably.

Coral quarantine tank

There is generally much less concern for quarantine when dealing with corals and other invertebrates, and generally, there is less of a problem with parasites in invertebrates than in fish. Also, many of the coral parasites are confined to specific host species or genera of hosts, whereas fish parasites, for the most part, reproduce quickly, spread to many different species of fish, and attain epizootic levels of infection in closed systems. But this doesn’t mean that an aquarist can ignore the potential for parasite problems with corals and other invertebrates.

One example of a coral pest that multiplies to plague proportions in a reef tank is Tegastes acroporanus, the so-called Red Bug. It is a parasitic copepod, small and rather flea-like, and it targets Acropora stony corals, sucking nutrients out of their flesh. One treatment used at Oceans, Reefs

& Aquariums (ORA) involve the use of dips in a dilute solution of iodine or in water containing a heartworm medication known as Milbemycin oxime (Interceptor) usually prescribed for dogs.

Quarantine procedures are not difficult to establish for corals and invertebrates; a second, smaller, well-lighted tank with high water quality will do the job, and it is wise to have this capability. Careful observation of any new acquisition is critical, especially if it comes from an unknown source. Be sure to observe the new coral at night a few hours after dark, since many parasitic organisms are only active during nighttime hours.

Hi, my name is Sean, and I’m the primary writer on the site. I’m blogging mostly about freshwater and saltwater aquariums, fish, invertebrates, and plants. I’m experienced in the fishkeeping hobby for many years. Over the years I have kept many tanks, and have recently begun getting more serious in wanting to become a professional aquarist. All my knowledge comes from experience and reading forums and a lot of informative sites. In pursuit of becoming a professional, I also want to inspire as many people as I can to pick up this hobby and keep the public interest growing.

Read more about Sean.

Please join also my Facebook group.